Overview

OverviewThe pelvis is a meeting point for multiple specialties such as urology, gynecology, medical and surgical gastroenterology, orthopedic surgery and physiotherapy. Chronic pelvic pain, often with urogenital, bowel or pelvic floor dysfunction, is a frequent problem across these disciplines. With the close relations between the pelvic organs and the visceral and somatic nerve plexuses in mind, it is not surprising that most cases of pelvic pathology have these symptoms in common. Because of the stigma and social isolation of these patients, it is not surprising that other associated problems may co-exist, such as depression, anxiety and prevalence for drug dependency. These pain conditions present a major challenge to healthcare providers because of their often-unclear origin, complex natural history and poor response to therapy. These sufferers will often approach several doctors and specialists in the hopes of finding relief. It can be an off-putting and long process as one failure after another can dash any hope of a permanent solution to their problem. In such cases, the goal then becomes to merely manage the pain and symptoms without ever seeking to investigate the root causes. Patients end up with widely varying diagnoses, depending on the particular specialty of the doctor they consult: “Idiopathic Sciatic Pain” or Chronic Low-Back Pain”, “Chronic Prostatodynia”, “Interstitial Cystitis”, “Vulvodynia” or “Irritable Bowel Syndrome” also known as IBS. With such diagnoses, patients are often sidelined and must content themselves to accept medical pain management and antidepressants, with their known side effects and risk of dependency, for the rest of their lives.

Specific diagnosis in pelvic neuropathies is therefore difficult and calls for detailed understanding of the neurology and neuropathology specific to the area, but these specialties are rarely involved. The clinical process is therefore hampered by deficient knowledge, together with insufficient methods for visualisation and intervention. We hereby suggest the introduction of Neuropelveology as a new discipline with focus on these problems.

Pathologies of the sacral plexus or other somatic nerves will produce pain on the affected nerve's dermatomes, with symptoms such as burning pain (allodynia), tingling, electric shock–like pain, numbness, and muscle weakness, along with urinary and bowel dysfunctions. The main symptoms of pelvic somatic nerve irritation are as follows:

The symptoms of pelvic neuropathic pain syndrome can include tingling, numbness and loss of feeling, weakness in the lower back, buttocks and legs, which has not been pinpointed to any traceable spinal cause. This scenario is rather widespread, with many patients not being able to achieve an accurate diagnosis of why they are experiencing pain and symptoms. “Pseudo-sciatica” of undetermined causes, is diagnosed when there are definitely no spinal sources responsible for causing the symptoms, yet a chronic expression is present. In these circumstances, no structural or non-structural cause has been verified as the source responsible for causing the sciatica. In precisely such cases, where the cause of the sciatica is of unknown origin, careful and thorough investigation of the portion of the sciatic nerve which lies within the pelvis and/or of the nerve roots of the lower spine, may offer an explanation as to the origins of the pain and the associated pelvic organ dysfunction. As yet though, this in-depth approach is still largely unknown in modern medical practice and training. This is all the more surprising, if one considers the variety of conditions affecting the pelvis region and also the many invasive procedures, which are carried out in close proximity to the pelvic nerves that could potentially induce compression or entrapment of the nerves or damage them in other ways. The number of such cases of pelvic nerve conditions is widely underestimated, mainly because of a lack of awareness that such lesions can exist and a failure to diagnose them appropriately. In the established field of neurosurgery the techniques for dealing with nerve lesions of the upper limbs are tried and tested but as yet, surgical exploration of the pelvic nerves remains largely uninvestigated by neurosurgeons.

Neurosurgical procedure techniques are well established in nerve lesions of the upper limbs but surgical exploration of the pelvic retroperitoneal area and the pelvic nerves is still uncommon. The only well documented pelvic nerve pathology is pudendal neuralgia (Alcock´s canal syndrome), probably because the nerve is easily accessible for neurophysiological exploration, infiltrations and surgical decompression. In contrast, endopelvic somatic nerves and especially the sacral plexus are difficult to access and have been less investigated in the past, although affection of these structures might explain some cases of chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

Neuropelveology has been introduced as a new discipline focused on pathologies of the pelvic nervous system and the possibilities for improved neurological diagnosis in chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Because of growing interest from the medical community, the International Society of Neuropelveology (ISoN) was founded in 2014 to provide universal access to education in this area.

Standard medical training imparts the concept that location of the pain and its etiology correspond to the same area. A classical workup usually follows two steps: determination of pain location followed by the determination of a potential etiology in the corresponding anatomical area.

The neuropelveological approach to pelvic neuropathies is primarily diagnostic with application of neurological principles and an absolute knowledge of the pelvic neurofunctional anatomy. Pathology of the visceral and somatic pelvic neuronal plexuses and detailed understanding of their properties, might explain a significant part of such unspecified pelvic pain and associated pelvic organ dysfunctions.

Therefore, patient history is the key with focus not only on pain location, but also on pain history, irradiation, aggravating factors, and vegetative and somatic symptoms. Taking the patient’s history is time consuming but enables in most cases the establishment of a potential diagnosis, which can be substantiated or rejected by the clinical examination. The first step is to evaluate whether the pain is visceral or somatic.

In somatic pain, it is essential to adopt a “classic neurological way of thinking” since location of pain and the site of potential, corresponding lesions can differ. Somatic pain is located superficially at the skin and is described as allodynia or electrical shock, with specific location, caudal irradiations to the genito-anal areas or to the lower extremities and lack of vegetative symptoms. The neuropelveological workup of suspected somatic pelvic pain follows then six steps:

Fig.1: Pelvic Congestion Syndrome of the uterus

Fig. 2: MRI- May-Thurner Syndrome

6. Final definition of the suspected etiology and proposal for the corresponding treatment. In many of these cases, an etiological diagnosis may be reached, and proper treatment instituted. However, this is a field where research into new strategies is needed.

Because somatic, neuropathic pain is quite specific, a neuropelveological workup typically allows for diagnosis of the lesion site in the pelvic nerves. Intervention in this area, which is covered by large vessels and a dense network of lymph nodes, has hitherto been hindered by the lack of minimally invasive surgical methods. However, development in video endoscopy has enabled exploration of the retroperitoneal pelvic space with access to the lumbosacral plexus. This has allowed for diagnosis of hitherto unknown local causes of somatic pelvic pain like vascular entrapment or local fibrosis secondary to previous surgery, and for nerve decompression or neurolysis performed in a one-step procedure. In case of axonal lesions, this endoscopic approach further permits laparoscopic implantation of neuroprosthesis (LION procedure) where electrodes are selectively placed in contact with the pelvic nerves. This might allow for control of pain, in parallel to neuromodulation in other peripheral nerves and the approach could also represent an alternative to current methods for sacral root stimulation. Moreover, recent studies indicate that the LION procedure applied to the sciatic and femoral nerves might engage residual spinal and peripheral pathways for recovery of voluntary motion of the legs in patients with chronic paraplegia secondary to spinal cord injury. These neuropelveological procedures should be reserved for experienced surgeons with special training in laparoscopic retroperitoneal pelvic surgery, but the diagnosis of pelvic nerve pathologies is accessible for all clinicians familiar with the neurological symptoms and signs specific to the area.

Lumbosacral radiculopathy is one of the most common disorders evaluated by neurologists and is a leading referral diagnosis for the performance of electromyography. In contrast, isolated sacral radiculopathies are estimated very infrequent in the literature and most manuals for neurology dedicate only few lines to them; most frequently reported etiologies are rare neurogenic pathologies and infiltrations by cancers while iatrogenic damages are estimated to be very rare due to the nerves being well-protected by the pelvic wall. The “neuropelveological “ reality is completely different: neuropathic pain secondary to pelvic surgeries, obstetrical procedures, chemo- and radiotherapy are commonly encountered problems in many medical offices. In the largest study of sacral radiculopathies to date, we reported that vascular entrapment of the sacral nerve root seems to be the most frequent etiology for non-neurogenic sacral radiculopathy followed by surgical pelvic nerve damage and more rarely, the deeply infiltrating endometriosis of the sacral plexus/sciatic nerve.

Awareness that endometriosis of the pelvic somatic nerves does exist has increased over the last few years, but lack of diagnosis and challenging surgical treatment means that it is still largely left undiagnosed. Sciatic endometriosis is not that common but should always be included in the diagnostic approach to pain and symptoms affecting the pelvic somatic nerves. Endometriosis of the sciatic nerve must be considered in the differential diagnosis in all young patients suffering from cyclical sciatic pain, especially when orthopedic and spinal conditions have been excluded. At the onset of the complaint, pain may begin just before menstruation and last several days after the end of flow. Left untreated, neuropathic pain will lose its cyclical nature, becoming constant and resilient to strong pain medications (opiates and neuroleptics). Endometriosis can affect the sacral plexus and/or the sciatic nerve in different ways. Endometriosis of the sacral plexus usually affects the nerves S2 - S4, responsible for an S2-sciatica, genito-anal pain (vulvodynia, pudendal pain, coccygodynie) and hypersensitivity of the bladder. Endometriosis of the sciatic nerve is by contrast located more distally, close to the great sciatic foramen and is likely to affect the cranial portion of the nerve responsible for a L5-S1-sciatica without genito-anal pain and urinary disorders. Because sciatic nerve endometriosis exposes nerve damage through deep infiltration of the nerve with axonal destruction, sciatic pain will be accompanied by sensory deficits in dermatomes L5 and S1 and motor deficits with weakness of the ankle (reduction of both dorsal and plantar flexion) and reduction of ipsi-lateral Achilles reflex.

Data that may prove the efficacy of medical/hormonal treatments over the long term do not exist. In the largest studies reported on more than 250 laparoscopic procedures for deeply infiltrating endometriosis of the sciatic nerve, all patients reported a systematic exponential worsening of gait disorders while neuropathic pain became resilient to initial drug treatments and drug-induced amenorrhea (blockade of menstrual bleeding) in just a few months or even weeks. According to these findings, to treat pain with drug-induced amenorrhea is legitimate, but as soon as gait disorders and foot drop appear, failure to advise surgical treatment is then unacceptable and even negligent because it exposes the patient to further irreversible neurogenic damage. Sciatic endometriosis may be treated the same way as deep infiltrating endometriosis of the pelvic organs by surgical resection. The classical neurosurgical approach from dorsal through the buttock does not offer a proper approach for treatment because endometriosis develops and grows within the pelvis; a dorsal approach will not permit complete resection of the pathology and recurrence is pre-programmed. Certified neuropelveologists are trained to perform laparoscopic procedures on the sciatic nerve and simultaneously have an in-depth knowledge of the disease of endometriosis, also affecting the sciatic nerve. It is thus very straightforward for a neuropelveologist to diagnose endometriosis of the sciatic nerve without any great effort.

The laparoscopic exploration of the sciatic nerve is therefore advised as soon as possible and before neurological disorders set in. Due to the fact that isolated endometriosis of the sciatic nerve does exist, laparoscopic exploration with exposure of the sciatic nerve has to be done systematically even when a laparoscopic inspection of the pelvis is normal and does not reveal any endometriosis of the endopelvic cavity.

Sciatic endometriosis is generally treated the same way as deeply infiltrating endometriosis of the pelvic organs: preferably the gold-standard laparoscopic exploration with excision by a skilled, minimally invasive pelvic surgeon who has vast experience in highly complex cases of endometriosis and neuropelveological surgery. Surgeons must always consider that to perform incomplete surgery and to leave the endoneural part of the endometriosis in place is to be avoided at all costs, since reoperations on the sciatic nerve only get increasingly complex, more dangerous and disruptive. In the case of deeply infiltrating endometriosis of the sciatic nerve, laparoscopic resection of the destroyed part of the sciatic nerve is required to obtain free margins. Current studies demonstrate that laparoscopic treatment can be done with successful results in terms of pain improvement and recurrence, and functional outcome is good so far as part of the nerve is preserved and patients are properly supported by intensive physiotherapy.

Video: Sciatic Nerve Endometriosis

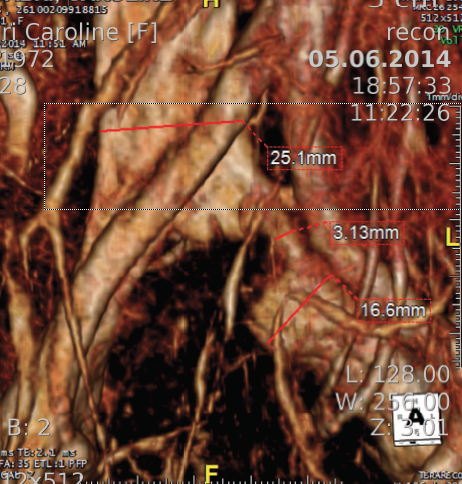

The feasibility of a surgical approach and a functional exploration of the endopelvic nerves by laparoscopy has significantly increased the awareness that pelvic nerve pathologies may exist and might be responsible for many intractable chronic pelvic pain conditions. One etiology that has recently become a focus of interest for the explanation of intractable neuropathic pelvic pain, is the so called “pelvic neuro-vascular conflict” as a result of the vulnerability of nerves as they pass in close relationship to the pelvic vessels. Neuro-vascular conflict is a patho-physiological phenomenon implicated in several pelvic neuropathies.

However, dilated veins alone, even ones close to nerves, do not induce neuropathic pain. Pain occurs only if the nerves are truly entrapped between two or more vessels, or between a fixed anatomical structure (ligament, bone, fascia, muscle...) and vessels, or by one or several vessels in a confined anatomical space. In a recent study of 97 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic exploration/decompression of the sacral plexus, three conditions were observed: pudendal neuralgia by compression at the lesser sciatic notch, the sacral radiculopathy S2-4 by compression at the infra-cardinal level of the sacral plexus and the sciatica L5-S1/2 by compression at the greater sciatic notch. Pain is aggravated by sitting, worsens during menstrual bleeding, during the Valsalva maneuver but does not wake the patient up at night, and is not accompanied by neurological dysfunctions. Laparoscopic exploration of the entire sacral plexus is essential to diagnose conflict. By intra-operative confirmation, laparoscopic decompression is a treatment of choice, based on the separation of the offending vessel from the nerves. These procedures are safe, with high rate of success; a neuropelveological approach is essential in terms of good treatment results with pain reduction >50% at 2years follow-up in 88.6% of the patients.

All pelvic, perineal and obstetrical procedures potentially expose patients to pelvic nerve injuries. Damages occurring during interventions (Primary Nerve Injury) are due to coagulation, suturing, ischemia or cutting and induce problems of sensation, pain and dysfunction starting immediately after the procedure or after a short interval of a few days. By contrast, nerve lesions of fibrotic tissue or vascular compression/entrapment (Secondary Nerve Entrapment) usually require several months or even years to develop.

The most frequently injured somatic nerve after pelvic surgery is the second sacral nerve root, especially on the right side, following anterior rectopexy and colposacro/ promontofixation and on the left side following fixation of the sacro-uterine ligaments; The second most frequent injury involves the sciatic nerve (left more frequently than the right) especially after pelvic lymphadenectomy and surgical procedures for genital prolapse. The lesions of the sciatic nerve are mostly on its caudal border in the infra-pyriform space, so that the pain is due to radiculopathy of S3 and S4 with the clinical combination of a partial sciatica, perianal and/or perineal pain and occasionally neuralgia of the inferior gluteal nerve (S2). Lesions of the inferior gluteal nerve are generally accompanied by lesions of the homolateral pudendal nerve and/or the sciatic nerve, while lesions of the superior gluteal nerve are mostly associated with lesions of the lumbosacral trunk and sometimes S1.

Implantation of sutures or mesh material or hematoma/abscess formation in proximity to nerves constitutes a risky situation for both primary and secondary nerve lesions. Transvaginal sacrospinous colpopexy is the classical high-risk procedure for pudendal nerve injury by direct lesion while suturing the sacrospinous ligament but also by entrapment when a hematoma or an abscess of the ischio-rectal space develops. Also interventions using mesh material for sacrospinal fixation, sacro-colpopexy or rectopexy may also expose patients to the risk of nerve damage. Laparoscopy is then a unique method for etiological diagnosis and neurosurgical treatment of such nerve lesions, by means of decompression or in the case of neurogenic lesion, selective implantation of electrodes to injured nerves for neuromodulation.

Video: Overactive bladder therapy

Video: Mesh complication - entrapment of the pudendal nerve left

Video: Endometriosis of the Sciatic Nerve with large infiltration of the pelvic sidewall

Video: Sciatic Nerve Endometriosis

Sacral plexus and sacral bone tumors often involve en bloc surgical resection with tumor-free margins and functional reconstruction challenges. Such a management is challenging because of difficulties in accessing the lesion, risk of causing damage to neighboring organs, and the risk of massive blood loss. In a posterior approach, due to first elevation of the sacrum allowing dissection of presacral structures, the risk for damage to intra-pelvic structures and hemorrhaging are especially high. The laparoscopic approach, by contrast, enables an optimal ventral approach with primary exposure of the rectum, the ureter and the pelvic nerves, making the procedure safe and probably much easier than the classical neurosurgical approach with less risk for postoperative functional morbidities and intraoperative hemorrhaging.

Video: Pelvic nerves schwannoma

Video: Osteochondrosaroma of the sacro-iliac bone

In our opinion, it is therefore reasonable to advise colleagues dealing with pathologies of the pelvic nerves to apply the neuropelveological principles in their clinical work. The International Society of Neuropelveology offers an e-learning program for the acquisition of the necessary knowledge, which is accessible to all physicians. This evolution in the management of patients suffering problems of the pelvic nerves requires increased communication between neurology, the pelvic clinical disciplines and basic research. Promotion of this process represents the aim of this new specialty: Neuropelveology.

Peripheral nerve tumors can occur anywhere in the body. Most of ...

Vulvodynia is a chronic pain syndrome affecting ...

Klausstrasse 4

CH - 8008 Zürich

Switzerland

E-Mail: mail@possover.com

Tel.: +41 44 520 36 00