Sciatica is a very common symptom with an incidence of up to 43% in a general working population. Sciatic pain is a highly prevalent cause of morbidity, with major deterioration of the quality of life with generally important social and professional consequences. Even when the sciatic nerve emerges from the sacral nerves root within the pelvic cavity, most common causes of sciatica mentioned in literature include pathologies of the lower lumbar and lumbosacral spine with herniated disk, bone spur on the spine or narrowing of the spine. When no vertebral pathology is found, sciatica is frequently designated as incurable or at least of unknown genesis. Intrapelvic causes of sciatica may then be omitted or limited to piriformis syndrome. Over the past two decades, improved insights in neuropelveology have led to the reporting of intrapelvic causes of sciatica, causes unknown in the past. Endometriosis of the sciatic nerve in women, vascular compression and surgical injury to nerves are the most frequent intrapelvic causes of sciatica.

Lower lumbar pain radiating into the buttock and the leg without focal neurologic deficit has a high prevalence in the general population. Sciatica is a relatively common condition with a lifetime incidence varying from 13% to 40%1, with societal costs alone likely to exceed $15 billion in the US.2 Sciatica is a highly prevalent cause of morbidity and poor health-related quality of life. Because the sciatic nerve (SN) provides direct motor function to the hamstrings, lower extremity adductors, and indirect motor function to the calf muscles, anterior lower leg muscles, and some intrinsic foot muscles, neurogenic damage to the sciatic nerve may induce pain but also difficulty in walking.

Although by definition sciatica happens when something presses or rubs on the SN or the sacral nerve root (SNR), most causes reported in the literature do not deal with the sciatic nerve itself but rather with pathologies of spinal cord: prolapsed intervertebral disc is the most common cause, followed by spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis or surgical scarring, trauma and tumors at the level of the lumbar spine3. All these causes may affect the sciatic nerve fibers contained in the spinal cord causing direct compression or chemical inflammation, resulting in sciatica. Only a few extra-pelvic pathologies of the sciatic nerve with etiologies such nerve damage secondary to surgical hip dislocation, arthroplasty and arthroscopy are reported in the literature.

Although the SNR and the SN are located within the pelvic cavity, intrapelvic etiologies are rarely studied and little reported in the literature. It is obvious that this omission in medicine can no longer stand. If one only considers how much pelvic pathology and surgical interventions in proximity to the pelvic nerves are done daily all over the world, the real incidence of pelvic nerve conditions is obviously widely underestimated. The only cited “intrapelvic cause” for sciatica is piriformis syndrome.

The situation has changed considerably since the introduction of laparoscopic surgery into the pelvic nerves field: Neuropelveology, a young discipline dealing with pelvic nerve disorders, has permitted the discovery of a multitude of intrapelvic causes hitherto very underestimated or even unknown4. All the limitations of access to the sciatic nerve for etiological diagnosis and surgical treatment within the pelvic cavity have been overcome with the introduction of laparoscopic surgery into the pelvic nerve field.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis is usually associated with a multitude of symptoms and constitutes a complex challenge to treatment. Awareness that endometriosis of the pelvic somatic nerves exists has increased over the last few years, but is still too little known in medical community.

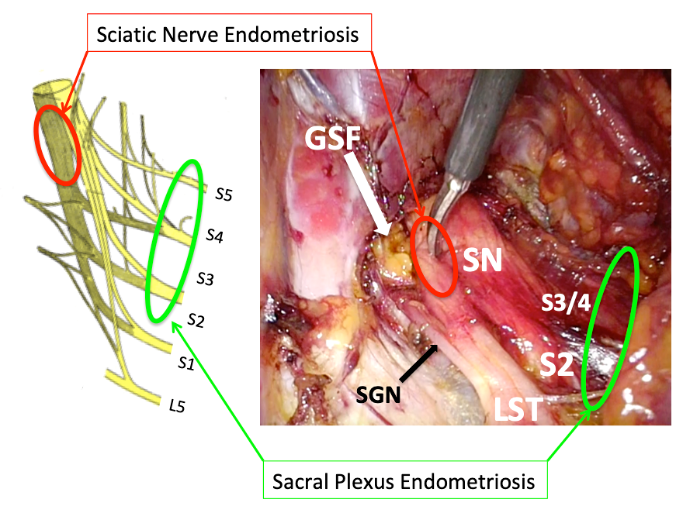

Endometriosis of the sacral plexus and of the sciatic nerve are two different entities with different clinical aspects:

Figure 1: sacral plexus vs. sciatic nerve endometriosis - locations of predilection for both form of somatic pelvic nerves endometriosis

SN: sciatic nerve – GSF: greater sciatic foramen – SGN: superior gluteal nerve – LST: lumbosacral trunk – S: sacral

Contrary to classical genital deep infiltrating endometriosis that progresses slowly, endometriosis of the SN is a rapidly progressing and aggressive disease, with the onset of neurological disorders by nerve destruction already apparent after 2 years. Endometriosis of SN must be considered in the differential diagnosis in all young patients suffering from cyclical sciatica with no identifiable spinal or musculoskeletal etiology. The cyclical nature of the pain is pathognomonic of the disease but only at the beginning of its evolution. The appearance of neurologic disorders of the lower limb, in particular difficulties in climbing stairs (foot drop), walking disturbances (Trendelenburg gait) and disturbances of the plantar flexion of the ankle (loss of Achilles reflex), are the main clinical signs. Transvaginal examination of the sacral plexus reproduces a massive trigger sciatic pain with a positive Hoffmann-Tinel sign. The disease can be visualized with MRI. Sciatic endometriosis may be treated the same way as deep infiltrating endometriosis of the pelvic organs by laparoscopic resection including nerve decompression and partial nerve resection. Such interventions are probably the most challenging surgery in the pelvis and may be reserved only for surgeons experienced in laparoscopic retroperitoneal surgery, multiple pelvic organs surgery and neuropelveological procedures. Laparoscopic treatment of pelvic nerve endometriosis can be done with great results in terms of pain improvement and low risk of recurrence, and functional outcome is good as long as part of the nerve is preserved and patients are properly supported by intensive physiotherapy8.

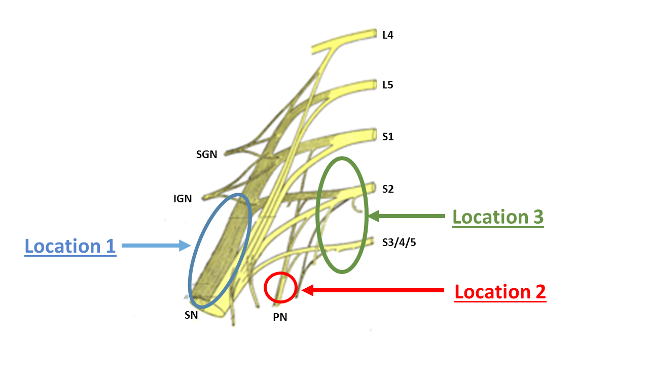

This condition corresponds to a nerve irritation (non-neurogenic condition) resulting from the vulnerability of the nerve as it passes close to vessels9. Dilated veins alone, even close to nerves, do not induce neuropathic pain. Pain occurs only if the nerves are truly entrapped between two or more vessels, or between a fixed anatomical structure (ligament, bone, fascia, muscle) and vessels, or by one or more vessels in a confined anatomical space. Three locations with a predilection for pelvic neuro-vascular conflict exist (Figure 2)10:

Figure 2: Sacral plexus – locations with a predilection for neurovascular conflict

SN: sciatic nerve – PN: pudendal nerve – SGN: superior gluteal nerve – IGN: inferior gluteal nerve – L: lumbar – S: sacral

All situations that increase venous blood flow (sitting, long standing, tricuspid insufficiency etc.) result in increased irritation of the nerves with increased of pain. In contrary situations that decrease venous blood pressure (lying, slipping, hypotonic treatments etc.) pain is improved. Because pelvic and leg veins are both exposed to risk of venous insufficiency by damaged valves, patients with varicose veins in the legs are also exposed to pelvic varicose veins. In addition pelvic interventions and pelvic/lower extremity thrombosis may promote changes in pelvic vein circulation and may induce pelvic neuropathy by vascular entrapment. It is also imperative to exclude both May-Thurner (Iliac vein compression) syndrome11 and nutcracker syndrome12, which may also be responsible for the development of pelvic varicose veins in proximity to the SN or the SNR. Both syndromes may be indicated by the discovery of uterine varicose veins predominant on the left side, visualized by vaginal ultrasonography with Doppler examination of the uterine vessels13. Because of the thromboembolic risks, the first step is to discuss with interventional radiologists whether or not endovascular intervention (embolization, angioplasty, stenting) is mandatory before making the decision to perform a nerve decompression procedure. The treatment of choice for vascular entrapment of the pelvic somatic nerves consists of laparoscopic exploration of the nerves with separation of the vessels from the nerves and their coagulation/transection14-16.

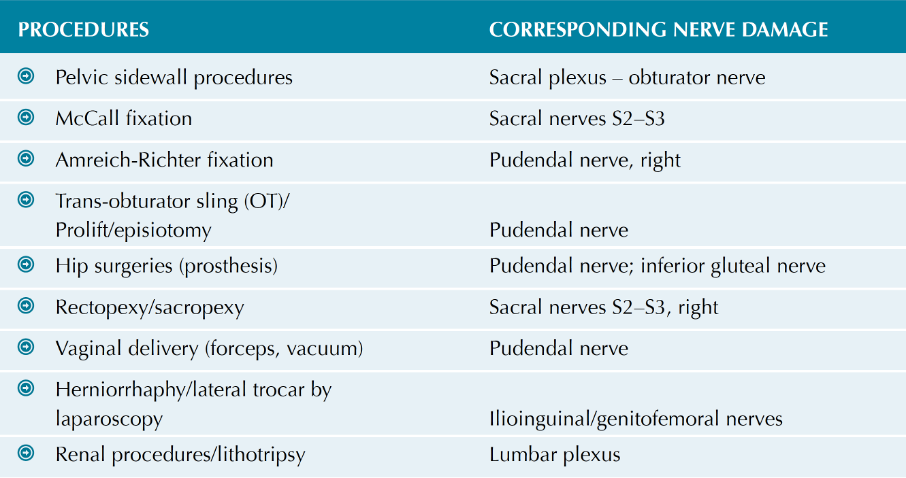

All pelvic, perineal and obstetrical procedures potentially expose patients to pelvic nerve injuries (Table 1).

Table 1: Pelvic surgical procedures with corresponding potential nerve injuries

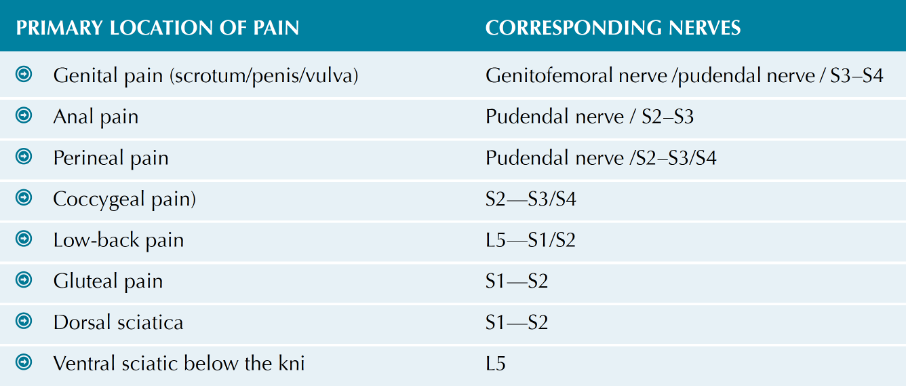

Real rates of pelvic nerve injuries secondary to pelvic surgeries are unknown due to database limitations, underdiagnosis or underreporting. Damages occurring during interventions are due to coagulation, suturing, ischemia or cutting and induce problems with sensation, pain and dysfunctions starting immediately after the procedure or after a short interval of several days. In contrast, nerve irritation due to scarring tissue secondary to pelvic surgery usually requires several months or even years to develop. The location of the pain does not reveal the location of the lesion, but which nerve is involved in the transport of pain information to the central nervous system (Table 2).

Table 2: Primary location of pain and corresponding nerve pathway

Transvaginal sacrospinous colpopexy is the classic high-risk procedure for pudendal nerve injury by direct lesion while suturing the sacrospinous ligament17 but also by entrapment when a hematoma or an abscess in the paravaginal space develops.18 More recent interventions using mesh material for sacro-spinal fixation,19 sacrocolpopexy or rectopexy may also expose patients to the risk of nerve damage.20 For these reasons, transvaginal mesh usage has been at the forefront of popular media and academic debate for the past 10 years, since the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 reported on serious neurogenic complications with surgical mesh for transvaginal repair of genital prolapse.

When the diagnosis of nerve lesion is made early after the procedure, treatment consists in the removal of sutures and/or mesh before massive fibrosis develops. If diagnosis is made after a long period of time, because dense fibrosis and/or atypical vessels (vascular entrapment) tend to develop, simple removal of the suture or mesh do not resolve the problem because the mesh-induced fibrosis remains, resulting in further nerve irritation. Treatment is based on laparoscopic exposure with decompression of the entrapped nerve(s), with partial removal of the mesh if required.21 Where axonal nerve damage has occurred, the LION procedure, which consists of laparoscopic implantation of a lead electrode to the injured nerve(s) for electrical neuromodulation, is the treatment of choice.22,23

Any neoplastic tumor of the pelvis and pelvic lymphadenopathies can induce pelvic neuropathy. Sciatica is then rather secondary and treatment consists in the treatment of the primary tumor or in nerve release by pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiotherapy applied to the pelvis may also damage pelvic nerves and cause refractory symptoms including sciatica. An enlarged uterus, especially in combination with a dorsal myoma or a uterine retroversion, can induce a mechanical compression of the SNR resulting in sciatica.

Management of pelvic tumors is always challenging because of difficulties in accessing the lesion and the risks of damaging neighboring organs (ureter, intestine, pelvic nerves). Among these complications, extensive hemorrhage is the most serious since it may threaten the life of the patient and jeopardize the outcome of the surgery.24 A laparoscopic approach permits an optimal analysis of the intrapelvic limits and extension of the tumor, and reduces the risks of intraoperative complications and postoperative functional morbidities by a primary exposure and dissection of the pelvic viscera (rectum, ureter etc.), a primary control of tumor blood supply and a selective preservation of all uninvolved pelvic nerves.

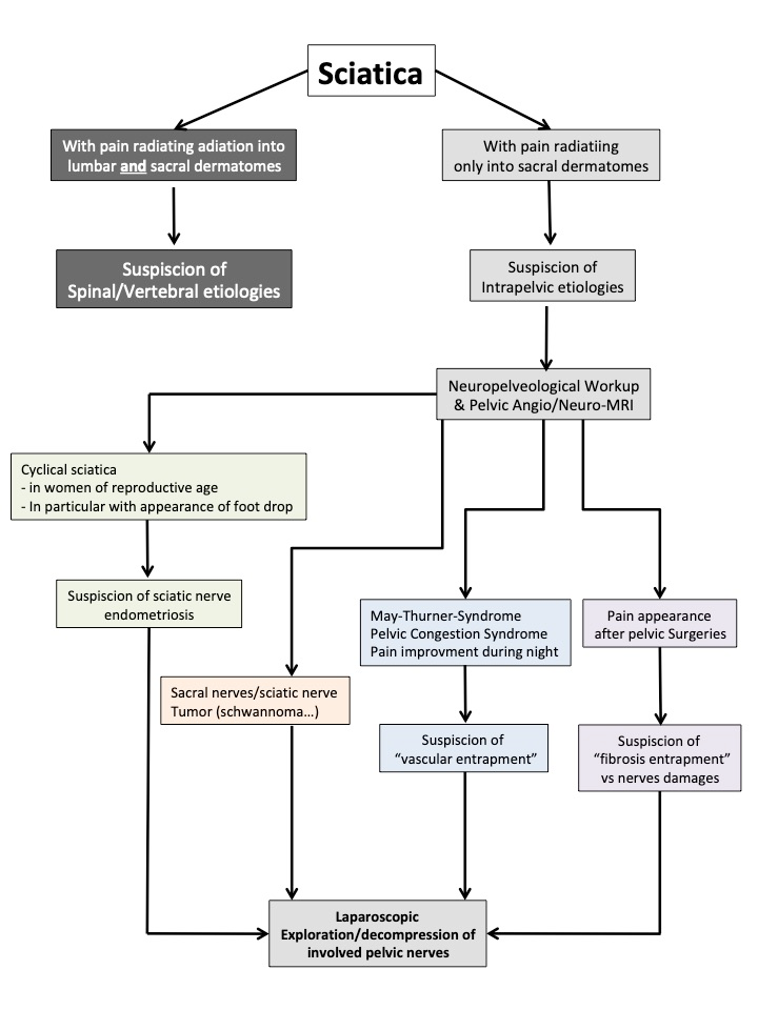

Because of the lack of awareness that pathologies of the pelvic nerves may exist, and probably because of limitations of access for neurophysiologic exploration and neurosurgical procedures, intrapelvic causes of refractory sciatica may be omitted in daily practice. Faced with refractory sciatica without obvious spinal etiology, especially when pain radiates only to the sacral dermatomes without any radiation to the anterior aspect of the lumbar dermatomes, it is imperative to determine an intrapelvic cause (Table 3). Diagnostic imagery permits the visualization of a possible pelvic tumor/endometriosis or pelvic varicose veins suspected of compressing the pelvic nerves (vascular entrapment). Cyclical sciatic pain in women suggests a potential endometriosis of the SN and especially when troubles in walking with, in particular, foot drop appear after two years of pain evolution. Absence of neurological deficits with improvement or even disappearance of pain during the night will be indicative of a possible vascular nerve entrapment. Finally, appearance of sciatica secondary to pelvic surgery will be suggestive of a possible surgical nerve lesion or fibrotic entrapment, especially when meshes for prolapse surgery have been used.

Table 3: Diagnosis and decision flow chart

Prof. Prof. DK Prof. Dr. med. Marc Possover, MD, PhD

...Prof. Prof. DK Prof. Dr. med. Marc Possover, MD, PhD

...Prof. Prof. DK Prof. Dr. med. Marc Possover, MD, PhD

...Prof. Prof. DK Prof. Dr. med. Marc Possover, MD, PhD

...Klausstrasse 4

CH - 8008 Zürich

Switzerland

E-Mail: mail@possover.com

Tel.: +41 44 520 36 00